Governor General’s Gold Medal

Three former U of T graduate students win 2020–2021 Governor General’s Gold Medal

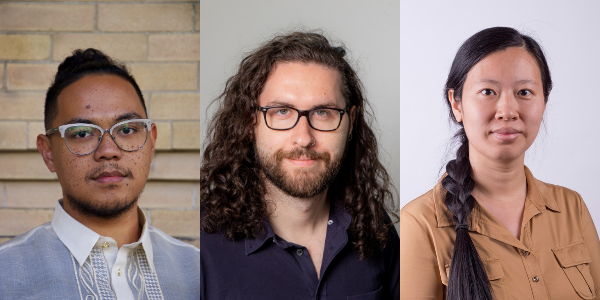

Three former U of T graduate students — Adrian De Leon, Andrew H. Proppe, and Yimu Zhao — have received one of the highest honours available to graduate students in Canada: the Governor General’s Gold Medal.

The Office of the Governor General annually awards Gold Academic Medals to students who achieve the highest academic standing at the graduate level. To be considered for the three gold medals available at the University of Toronto, candidates must be nominated by their graduate units.

Meet the winners

Adrian De Leon (PhD History, 2019)

Adrian De Leon won his first ever research grant when he was a third-year undergraduate student at the University of Toronto Scarborough. The English major had developed an interest in Filipino American literature, but worried that his work might be dismissed for being “mesearch-y” under the dominant academic paradigms. “No such thing,” replied his supervisor, then-Associate Professor Marjorie Rubright, now at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, whom De Leon credits with being his first research mentor.

That realization marked a turning point for De Leon, who has since gone on to win a Fulbright Scholarship, a SSHRC Bombardier scholarship, and now, a Governor General’s Gold Medal, for his work on Filipino American histories. The Assistant Professor of American Studies & Ethnicity at the University of Southern California says he’s pleased—and surprised—to have his alma mater recognize his doctoral work. “This is a project about Asian America that won Canada’s most prestigious award,” he muses. “I never expected my work to be legible in Canada.”

De Leon earned his PhD from U of T’s Department of History in 2019, where he wrote a dissertation on the production of race and indigeneity through the plantation economy of Northern Luzon, paying attention to Native histories of migration and labour that preceded US colonialism in the Philippines. “Diaspora, empire, and nation — these things look different from the places empire and nation call marginal,” he reflects, adding that the word “boondocks” comes from a colonial corruption of the Tagalog word “bundok,” meaning mountain or hinterland. “I wanted to write a history of the world from the boondocks.”

But not everyone shared Professor Rubright’s early enthusiasm for her student’s interdisciplinary approach, which deviated from the methodologies of a traditional History program. Some former mentors discouraged De Leon from pursuing his project, arguing that his work would make him little more than “a diversity hire.” Others told him that Ethnic Studies wasn’t a real discipline, and that he’d have a difficult time finding a job. “To be a scholar of colour from a working-class background and be told repeatedly that you have to do things a certain way — which I read as a white male way — it was harrowing,” he recalls.

Despite that experience, De Leon, who is the author of two poetry collections and co-editor of FEEL WAYS: A Scarborough Anthology, says he’s thankful for the encouragement of his supervisor, Professor Takashi Fujitani and his mentors, Associate Professors Kevin Coleman and Robert Diaz, all of whom influenced his thinking and research. But what he really wants to see in Canadian academia is a willingness to question the ways in which knowledge has been constructed.

“The University of Toronto needs Ethnic Studies,” he said in a pre-recorded acceptance at the SGS virtual awards ceremony on April 22, which he attended with his family. “Our institution needs a curriculum that takes seriously the intersections of race, gender, sexuality, and class together in doing work in the service of our communities.”

Andrew H. Proppe (PhD Chemistry, 2019)

Andrew Proppe always had an inkling that he would find his way into academia. “My girlfriend likes to make fun of me for this, but my dad’s a professor and that was always hugely inspiring to me,” says the Governor General’s Gold Medal winner whose father, Dr. Harald Walter Proppe, has taught mathematics at Concordia University for more than 50 years.

The younger Proppe developed a love for the sciences thanks to a trio of “amazing” physics, chemistry, and math teachers in high school. But when he approached his father for advice on choosing between a degree in Physics or Chemistry, the mathematician told him not to pursue the former because he wouldn’t be able to find a job. “I thought that was funny coming from the math professor,” he laughs.

Nonetheless, Proppe took his father’s advice, opting to study chemistry at Concordia University as an undergraduate student. before earning his PhD in Physical Chemistry from the University of Toronto under the supervision of professors Ted Sargent and Shana Kelley.

Despite his early passion and stellar academic record, Proppe never expected to win a Governor General’s Gold Medal. “I’m really humbled and very surprised, just because of the quality of research happening at U of T,” he says. “It’s a great honour.”

Proppe attributes his success to the support of his supervisors as well as his close-knit community of friends and collaborators at U of T. “Part of the reason I enjoyed my PhD so much in Toronto was that there was such a sense of community in Ted’s lab,” says Proppe, who was one of a cohort of five doctoral students working in Sargent’s lab. “Even when experiments weren’t going well, it was nice to come in to work.”

Proppe’s work at U of T focused on the development of next-generation materials for solar cells. In particular, he was interested in improving the efficiency of metal halide perovskites, next-generation materials that can approximate silicon’s energy-conversion capabilities without requiring its high temperature processing.

“With silicon you have to heat it up to very high temperatures to get these near-perfect, defect-free crystals or ingots to turn into solar cells, which is expensive,” he explains. “But metal halide perovskites are these things that come in a vial. You can slather them onto a film, heat it up a bit, and they form into materials with these amazing power conversion efficiencies.”

Now an NSERC postdoctoral fellow at MIT, Proppe continues to work on metal halide perovskites and their applications for quantum computing and quantum security protocols. Though he’s enjoying life in Cambridge, the Montreal native has his eyes set on a faculty position back home in Canada. “As nice as it is to be in Cambridge, I do miss Canada. I never envisioned a life not living there.”

Yimu Zhao (PhD, Biomedical Engineering/Medical Engineering, 2019)

You know Yimu Zhao is passionate about her work when she says cardiac tissues are “energetic.”

The U of T alumna, who earned her PhD in Biomedical Engineering under the supervision of Professor Milica Radisic, specialized in engineering cardiovascular tissue on an Organ-on-a-Chip platform for her doctorate. And why does that matter? “We can take a skin cell from a patient with a specific disease, reprogram it into a stem cell, then differentiate it into all kinds of cells including the cardiac cells,” she explains. “Then we can use this patient-specific tissue to test if a drug is effective or unsafe.”

If that wasn’t impressive enough — Zhao has also contributed to 18 peer-reviewed publications, six of them as a first author. (One of her articles appeared in the pre-eminent life-sciences journal Cell.) She’s also one of the student co-founders of TARA Biosystems Inc., to which her invention is patented and licensed.

Zhao, who says she used to recite her middle-school science textbooks from memory, has always wanted to be a scientist. She was thrilled to learn she had received the Governor General’s Gold Medal. “I’m incredibly honoured,” says Zhao, who holds a bachelor’s and a master’s in chemical engineering from Western University and Queen’s University respectively. “It makes me feel proud of my work.”

The mother of three says she wouldn’t have been able to juggle the demands of a family and a doctoral program without her supervisor’s support. “Lack of support can be a huge barrier, says Zhao, who had two of her children over the course of her doctoral program. “People usually want to start families around the time they start their PhDs. But I know so many students who can’t afford to, or simply don’t have the energy.“

She says her supervisor offered lots of flexibility and also helped her apply for funding. I’m extremely appreciative of my mentor’s support,” she continues. “It’s a wonderful example of women in STEM supporting other women.”

Zhao is currently an NSERC postdoctoral fellowship at Columbia University, where she’s working with Dr. Gordana Vunjak-Novakovic, who also served as doctoral supervisor for Zhao’s mentor, Dr. Radisic. “You could say I’m in the lab of my academic grandma,” she laughs. She says her new environment is also radically supportive.

Zhao is working remotely from Toronto to be close to her family, but hopes to find a faculty position when she’s finished. “I really enjoy research,” she says. “I hope I can have my own lab one day.”