Supervision Guidelines for Faculty – Section 3: Supervisory Styles

While some aspects of good supervision can be considered universal, and should be adopted by everyone, supervision styles may vary across graduate units and disciplines. In addition, as a supervisor you may have your own unique style of supervising your graduate students. As long as this style respects the more general best practices, this is a good thing. It is important, however, that faculty members are cognizant of their own strengths and weaknesses as a supervisor in order to find the best way to support their graduate students.1 Indeed, the process of evaluating one’s own supervisory style can make faculty more effective supervisors.

There is no one-size-fits-all model for supervision.

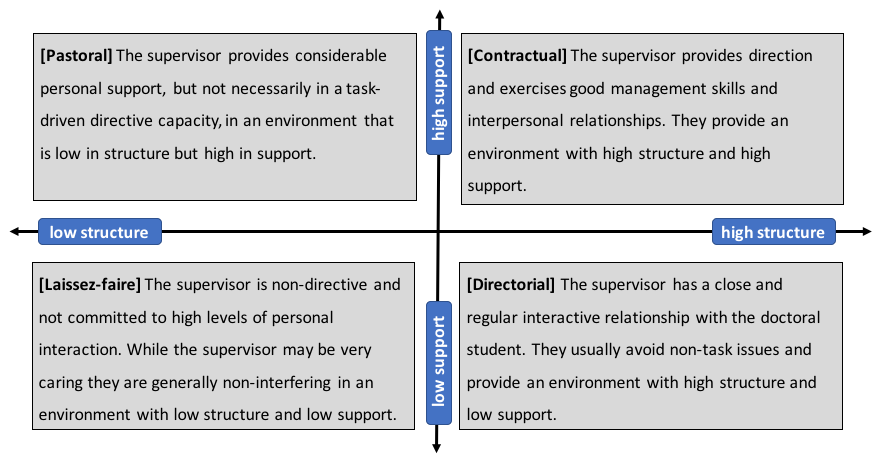

Figure 1: The following figure is adapted from Figure 1 in Gatfield (2005). We believe it may be helpful as a starting point for reflecting on one’s supervision style.2

The model proposed by Terry Gatfield in 2005 provides an overview of supervisory styles ranging from laissez-faire to pastoral (both of which necessitate greater student independence), to contractual and directorial (which provide greater supervisor direction to students). The “structure” axis reflects those components in the supervisory relationship that are provided primarily by the supervisor(s) in negotiation with the candidate. They reflect the management process of graduate supervision, and include such elements as topic selection, meeting schedules, setting of milestones, feedback turnaround time, and writing support. The “support” axis includes the components supplied by the institution and supervisors that are non-directive and optional. This axis includes such elements as sensitivity to student’s needs, confidence building, exposure to academic discipline, office and lab space, policy manuals, funding, and statistics support.

The model also provides a helpful way to understand reasons why a supervisory relationship may become unsatisfying for both the supervisor and the student. For instance, a student seeking higher levels of support and structure may feel unsupported and neglected by a supervisor who has a more laissez-faire approach to supervision. Alternatively, a supervisor who takes a more directorial approach may lead some students to feel a lack of autonomy and trust in the supervisory relationship.3

An important feature of Gatfield’s model is that it places supervisors and students on a spectrum, using descriptors to identify what he refers to as “preferred operating styles.” This means that although a supervisor might have a propensity toward one particular style over another, it allows for movement between styles as necessary. Individuals may find themselves on different parts of the spectrum at different times during the degree or supervision process. For instance, a supervisor may allow the student lots of flexibility early in the doctoral program as the student tries to identify a suitable topic (more pastoral), but become more directive and contractual as the student is actively pursuing the project. Later in the program, the supervisor again may become less directive or prescriptive as the student is focused on writing the thesis.

Gatfield stressed that none of the four styles should be considered inherently undesirable or wrong. Supervision strategies are only ineffective if they do not match the needs and expectations of the supervisor and student.

Supervision Across Different Disciplines

Ben is in his second-year as a PhD student the Department of History. He has been asked by his supervisor to come back in six months with a proposal for his research project. He usually meets his supervisor once every six months, but is welcome to request earlier meetings, if helpful.

Elizabeth is doing her PhD in a chemistry lab as part of a funded project. She is expected to attend biweekly lab seminars with her supervisors, other students in the lab, and postdoctoral fellows to discuss her research progress. In addition, she often meets with her supervisor informally throughout the week to discuss her work.

The University of Toronto offers many graduate degree programs, spanning the various fields and disciplines within the humanities, social sciences, physical sciences, engineering, and life sciences. All research degree programs and a number of professional programs require that students engage in some form of research under the supervision of a faculty member.

Given the variety of programs and disciplines, it is not surprising that one can find considerable variation in supervision across the University. For instance, in some research-stream programs, graduate students are expected to develop their research project quite independently from the supervisor, while in other programs or research groups, a student is expected to develop a project that fits within ongoing research projects in the supervisor’s laboratory or research group.

The nature of the interaction between the supervisor and student also may change throughout a student’s program. For instance, some supervisors may interact and give guidance to students fairly regularly (e.g., daily or weekly) during the first stages of the program but expect students to work very independently on their project, receiving only occasional guidance towards the end of the program. Furthermore, in some programs, faculty members may agree to supervisor a student prior to admission (and indeed, this may be an admission requirement of the program). In other programs, a student may be admitted and asked to identify a supervisor within the first year of the program. In yet other programs, students initially may have an advisor but a supervisor is only identified or assigned upon the student’s completion of their qualifying exams.

Research across North America has consistently shown that effective supervision and mentorship are the most important features of a student’s graduate school experience, and indeed are major factors in driving program completion or attrition.4

The research has shown that students across every discipline value supervisors who are:

- Accessible: Supervisor meets with students frequently in both individual and group settings.

- Approachable: Supervisor creates a comfortable environment where students could discuss concerns.

- Encouraging: Supervisor provides research support, guidance, and motivation.

- Interested: Supervisor is interested in the student and wants to know them as individuals.

- Open and flexible: Supervisor discusses expectations and conflicts openly and honestly and adjusts to students’ needs over time.

- Professional: Supervisor facilitates the student’s socialization into the program and discipline, encourages participation in conferences, and introduces students to people in the field.

- Supportive: Supervisor provides professional and career development support.5

Notes

- McIntosh, M., “Promising Practices in Graduate Supervision in a Canadian Context: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis of Existing Research,” Unpublished report (University of Toronto, 2016), 4-7.

- Gatfield, T., “An Investigation into PhD Supervisory Management Styles: Development of a dynamic conceptual model and its managerial implications,” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 27.3 (2005), 311.

- McIntosh, 4-7.

- Council of Graduate Schools, “Ph.D. Completion and Attrition: Findings from exit surveys of Ph.D. completers,” (Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools, 2009). Retrieved from: https://cgsnet.org/phd-completion-and-attrition-findings-exit-surveys-phd-completers-0

- McIntosh, 9.

Sections

Section 1: Introduction

Key topics: How can these guidelines help you?

Section 2: Supervision and Mentoring

Key topics: Defining key terms; General characteristics of good supervisory practice; Effective supervision and mentorship strategies

Section 4: Effective Supervision in Practice: From the Initial Stage to Finishing Up

Key topics: Agreeing to Supervise a Student; Setting up a Committee; Program Timelines, Good Progress, and Academic Standing; Funding; and Submitting the thesis for the Final Oral Examination

Section 5: Supporting Students to Completion and Beyond

Key topics: Guiding principles that may help your student through the final stages of their PhD; Graduate Professional Development and career preparation

Section 6: Creating Equality and Equity When Working with Students

Key topics: Defining “equality” and “equity”; How experiences of grad school differ among students; Considering students’ backgrounds (e.g., students with family responsibilities, First Nations students, international students, students with mental health issues, students with writing support needs, etc.)

Section 7: When a Student May Need Accommodations

Key topics: Accommodations vs. time-limited academic adjustments; Defining “accommodations”; Disclosure and Confidentiality; Available resources

Section 8: When Problems Arise

Key topics: Identifying potential sources of problems in the student/supervisor relationship; Who can you talk to?; Vignettes