Graduate Funding at the University of Toronto

In the Fall of 2022, the School of Graduate Studies (SGS) struck the SGS Graduate Funding Working Group. Chaired by Dr. Joshua Barker, Vice-Provost, Graduate Research and Education and Dean of SGS, the working group was formed to collectively enhance understanding of the graduate funding landscape at the University of Toronto (U of T) and identify strategic recommendations to address ongoing issues related to graduate funding and improve alignment and transparency across the University, where possible. (photo by University of Toronto)

Reports

1. Overview of Graduate Funding at University of Toronto

SGS Graduate Funding Working Group

School of Graduate Studies

Fall 2023

Table of Contents

The School of Graduate Studies (SGS) regularly conducts a survey titled the Graduate Student Experience in the Research University (gradSERU), to collect feedback about graduate students’ experiences at the institution. The survey seeks graduate student perspectives on various topics related to student experience, including reasons for selecting University of Toronto (U of T), satisfaction rates, research and educational experience, health and wellness, and financial support, among others. Results of the gradSERU survey assist SGS in understanding student needs and in identifying areas for improvement in programming, services, and support resources. By agreeing to conduct the gradSERU survey, U of T became part of the SERU consortium, a collective of international peer institutions that also administer the SERU survey consistently. Through membership in the SERU consortium, U of T can assess survey results in relation to the aggregate results of other leading research institutions in the network.

A review of the 2021 gradSERU results revealed a concerning trend in relation to graduate student funding at U of T: graduate students in research-stream programs at U of T reported the lowest levels of satisfaction with financial support compared to all other peer institutions in the SERU network.1 In addition, U of T research-stream graduate students were among the most concerned with costs of education, housing expenses, and ability to pay off debts upon completion of their programs.2 Moreover, they also suggested that the level of financial support received had impacted their studies, with 37% indicating inadequate financial support as a significant obstacle to their academic progress.3

In response to these results, SGS established in the Fall of 2022 the Graduate Funding Working Group – composed of Vice-Provosts, Associate Deans and Vice-Deans Graduate, graduate faculty members, graduate students, and staff from graduate education, financial aid and awards, and planning and budget offices. The working group was created to strengthen understanding of the graduate funding landscape at U of T by engaging in a variety of measures, including: reviewing current policies and practices in graduate student funding across the institution; exploring student experience data, current issues, and associated implications for all stakeholders; assessing U of T’s funding support in relation to peer institutions in Canada and abroad; and identifying existing institutional levers for improving graduate student funding levels. Through the review of relevant institutional data and robust discussions, the working group aimed to identify a series of funding considerations and strategic recommendations that academic divisions and graduate units could employ to attract and retain talented students and establish best practices to support students during the course of their programs. Group discussions were framed around the core goals of improving equity, enhancing competitiveness with peer institutions, elevating graduate student experiences, increasing clarity and transparency around graduate funding, and supporting the SGS mission of promoting University-wide excellence in graduate education and research.

This comprehensive report was created in response to the Working Group’s recommendation to summarize the insights gained through this cross-campus collaboration and develop an accessible institutional resource that can help the U of T community to increase their knowledge and understanding of graduate funding. The document provides a broad overview of the current state of graduate funding in Canada, an outline of graduate funding policies and practices within U of T, and the challenges associated with these practices in a decentralized context. By providing this comprehensive overview, we hope to illustrate the possibilities, challenges, and limitations for improving graduate funding at U of T.

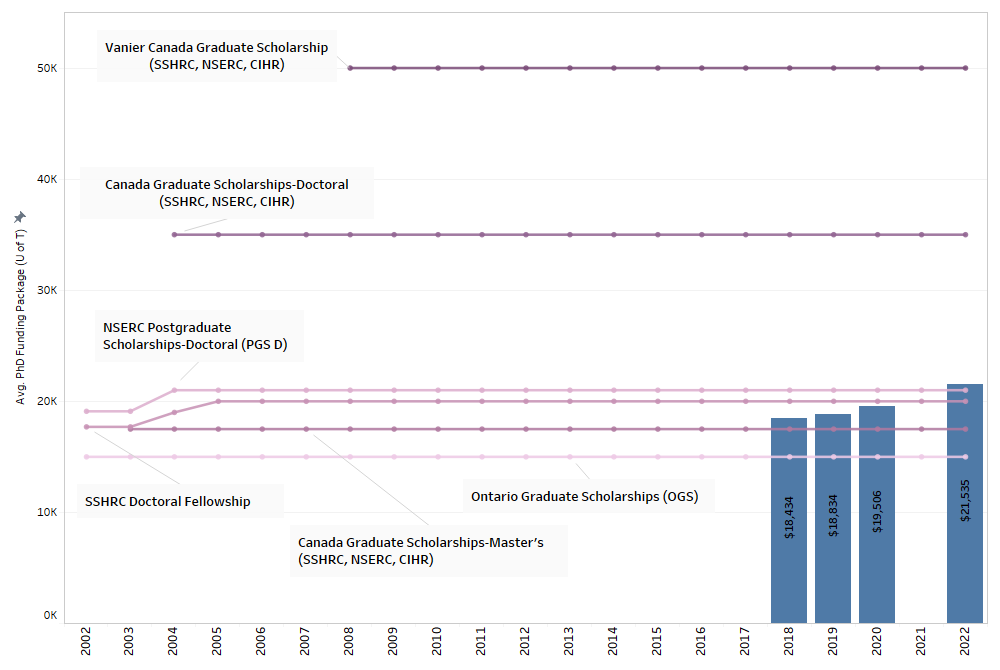

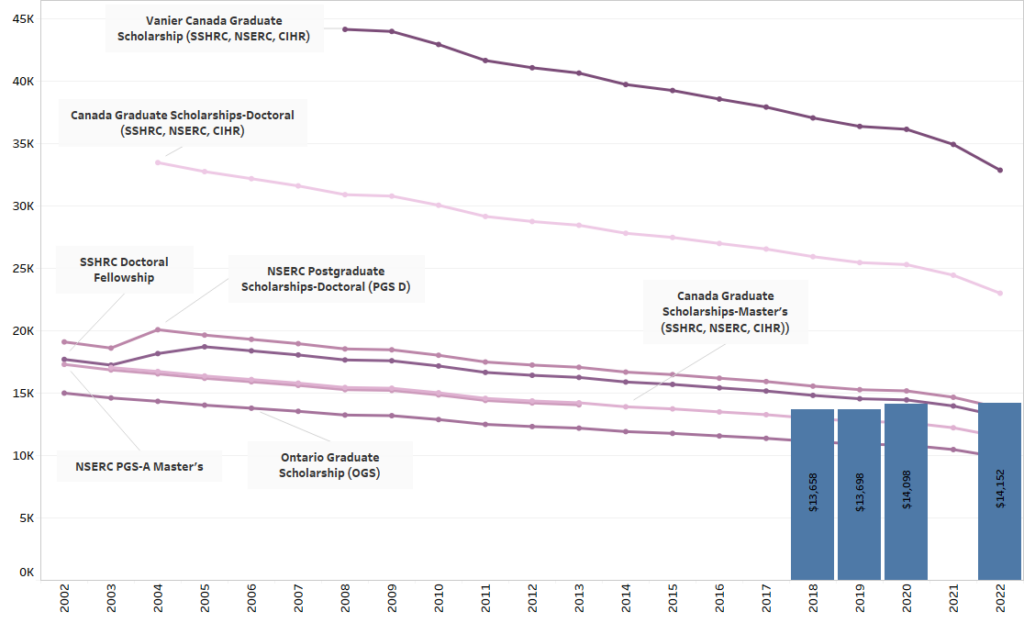

Canada is at an inflection point for research funding.4,5 Research investment in Canadian institutions is not keeping pace with that of peer nations, as stated in a recent U15 Canada press release: “…Peer countries like the United States, Germany, and the UK are making game-changing investments to advance knowledge and develop the highly qualified talent that underpins all efforts to build a better future.”6 A lack of significant investment has also meant that the value and number of tri-council research scholarships and fellowships (e.g., NSERC, SSHRC, CIHR) for graduate students and postdoctoral researchers has remained relatively static over the past twenty years,7, 8 and that the level of funding through scholarships has not risen with the cost of living or kept up with global graduate-trainee funding trends.9 A recent report from the Advisory Panel on the Federal Research Support System also suggests that insufficient funding in the Canadian research system restricts the ability to attract, train, and retain the brightest, most talented students, both from within Canada and abroad.10 Anecdotal evidence further supports this finding, with some Canadian students reporting that they opted to complete doctoral programs in the United States due, in part, to what they perceived to be a better graduate funding package.11

The challenge of providing competitive funding packages is particularly pronounced in the U of T context. As many of our disciplines (and the University more broadly) garner elite global reputations,12 the University finds itself increasingly in direct competition for the world’s best students with some of the top institutions worldwide. For instance, the 2023 QS World University Rankings by Subject ranked U of T in the top 25 in 34 subjects, recognizing U of T alongside a select group of schools including Cambridge University, Harvard University, University of Oxford, Stanford University, and University of California, Berkeley.13 While it is difficult to establish dollar-for-dollar funding package comparisons for a number of reasons,14 feedback from graduate chairs and administrators suggests that current funding levels at U of T make it difficult to compete with these institutions for top talent. The challenge is acute when peer programs are situated in privately-funded universities or in publicly-funded institutions that have made significant increases to their funding packages or operate in lower-cost markets. In this environment, it is more important than ever that graduate units engage in ongoing assessment of their funding policies and practices vis-à-vis their discipline-specific peers.

While funding is important for attracting top talent, it is also critical to student success in our programs. A recent study of 1,305 graduate students in Canada found that financial stress was a significant concern, with students worried about low wages, affordability, and costs of living, as well as the debts incurred during graduate studies.15 The gradSERU 2021 survey indicates that graduate students at U of T share these concerns.16 Similarly, recent discipline-specific analyses have found that current graduate funding stipends do not adequately cover the cost of living expenses in Toronto, one of the most expensive cities to live in Canada.17,18 To make ends meet, many students take on loans, rely on personal savings or support from family members, or seek out additional employment opportunities,19,20 straining their mental health and compromising their progress through their programs. Affordability challenges can be exacerbated for international graduate students as they can have increased educational costs and are ineligible to apply for some of the major awards available to domestic students, including tri-agency scholarships. Graduate chairs anecdotally report that at an aggregate level such concerns can also negatively impact the overall climate in a department, which in turn damages student-faculty relationships.

Together, these considerations demonstrate an urgent need to directly address the challenges of appropriate and sustainable funding supports for graduate students. It is a particularly important issue given the critical role graduate students play in enhancing the University’s research prowess and reputation on the international stage. Every year, U of T awards degrees to ~850 PhD students and another ~1,375 research master’s students. Many of these students contribute substantially to the University’s research productivity through their publications and other achievements. They are also some of the University’s most important ambassadors for its research mission in academic institutions across Canada and around the world, as well as in industry and government. Most students will look back on their graduate experience as having defined their subsequent life trajectories. It is imperative that they are given an optimal experience while they are here.

Despite a common desire among virtually all University stakeholders to improve graduate funding, there are significant hurdles to be overcome. As we discuss below, the University relies heavily on government support to sustain its graduate student funding packages and this support has been flatlined for many years. While we must continue with our robust advocacy to government on this front, we must also do what we can to make better use of existing resources. This will require concerted efforts by all levels of the graduate community – academic divisions, institutional administration, graduate units, faculty members, and graduate students – to work cooperatively and coherently with one another to improve graduate student funding practices overall, while also acting within their own domain to identify available resources, use them efficiently, and deploy them to maximize graduate student funding possibilities. To do so, it is imperative that we develop a shared understanding of the policies, practices, and sources of graduate funding as they currently exist, as well as the levers we have at our disposal for making changes going forward.

At U of T, the overarching principles pertaining to graduate funding come from the Governing Council policy on Student Financial Support, which states that “no student offered admission to a program at the University of Toronto should be unable to enter or complete the program due to lack of financial means.”21 Under this policy, access to financial supports for students is paramount and is considered to include restricted funds, funds comprising the Ontario Student Opportunities Trust Fund (OSOTF), or funds allocated through the operating budget of the University, including awards outlined in the Policy on Student Awards. Examples of financial support for students include grants, bursaries, scholarships, loan programs negotiated by the University with other financial institutions, and graduate teaching and research assistantships.

Through this policy, Governing Council provides general financial support and resource parameters according to a student’s status (e.g., full-time/part-time, domestic/international) and the type of program in which a student is enrolled (undergraduate programs, professional programs, and doctoral-stream programs). At the graduate level, the policy outlines the goal of providing full-time doctoral-stream students with multi-year packages of funding support that are competitive with the financial support offered by peer institutions. For professional graduate programs, the policy requires students to self-fund and/or seek financial support from the Ontario Student Assistance Plan (OSAP), with any remaining unmet financial need by OSAP to be addressed through a variety of grants or other institutionally negotiated loan programs.

Although Governing Council sets the overall University policy, the processes for determining availability, composition, sources, and annual amount of graduate funding over the span of a student’s enrollment in a given program are not uniform across the institution. Instead, guided by the policy on Student Financial Support and the University’s annual operating budget22 (based on the University’s strategic priorities), graduate funding levels are predominantly determined by academic leadership in each of the academic divisions and the corresponding graduate units.23 Funding levels are based on a unique combination of factors, including but not limited to, academic division budgets, student recruitment, research foci and needs of faculty members, primary investigator/supervisor grants, program enrollment, time to degree completion, and other available resources. As a result, the amount of each program’s funding, the composition of the funding package, and the number of years in which funding is offered, vary across the University (within specific institutionally-established constraints). In addition, graduate students are expected to play an active role in funding their graduate studies by applying for major scholarships (e.g., NSERC, SSHRC, CIHR), pursuing research or teaching assistantships, and seeking additional financial support opportunities in their field of research (e.g., external grants, fellowships).

The role of SGS in graduate funding is to serve as a resource for academic divisions and graduate units by:

- providing best practices for internal and external communication regarding graduate funding;

- ensuring funding decisions are in alignment with the University’s strategic priorities;

- assisting in the coordination of funding levels across graduate units on an ad-hoc basis;

- liaising with Labour Relations regarding teaching assistantship collective agreements as well as with the graduate community to ensure compliance with collective agreements in relation to employment income; and

- acting as an avenue for students to escalate concerns or issues related to their own graduate funding packages in the event that their concerns were unable to be addressed at the graduate unit and academic division levels.

SGS also conducts institution-wide research to assess issues and experiences pertinent to graduate students – including graduate funding – and strives to provide up-to-date data to graduate units and academic divisions to guide decision-making. In addition, as a central service for graduate studies, it adjudicates and disburses over $70 million annually for external and internal graduate and postdoctoral awards.

The Funding Package: Base Funding Commitment vs. Actual Net Income

Full-time PhD-stream students typically make up what is known as the funded cohort at the University – a group of students enrolled in a graduate program for whom there is an institutional commitment to provide funding packages throughout the duration of their published program length. In addition to programs in the funded cohort, there are also some programs outside of the funded cohort that provide partial funding – in both duration and levels of funding – to the students in their programs.

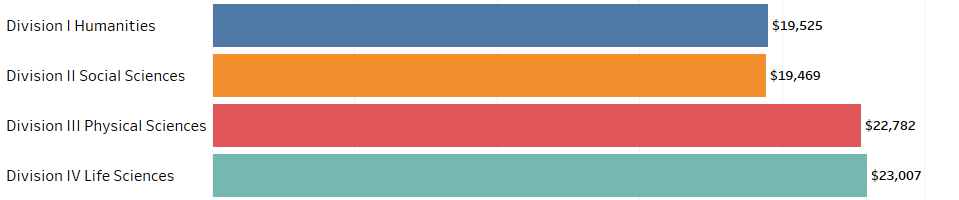

When developing funding packages, most graduate units articulate an overall base funding commitment to all students enrolled in the program. For the purpose of this report (except where noted), base funding refers to a graduate unit’s minimum funding commitment to each student per year, including tuition costs and annual living stipend, during the funded portion of the program (e.g., first 4 or 5 years of a PhD). Base funding information is communicated to students at the time of admission and on an annual basis thereafter. Figure 1 demonstrates the average base funding packages offered by SGS Divisions in 2022-2023, excluding tuition support.

Figure 1: Average Base Funding Packages for Funded Doctoral Programs by SGS Divisions in 2022-2023

A base funding commitment limited to the published, expected length of a program can be problematic, as many students extend their studies beyond the recommended time frame for a number of reasons, including life circumstances and events, research and teaching responsibilities, preparation for an unpredictable and highly competitive job market, the structure and/or culture of the program, or unanticipated challenges in the research phase. As a result, students may be left without guaranteed income and may elect to undertake additional paid work (e.g., TAships/instructorships, outside employment) that can further delay their academic progress in the latter years of their research programs. This issue must be reviewed and addressed moving forward.

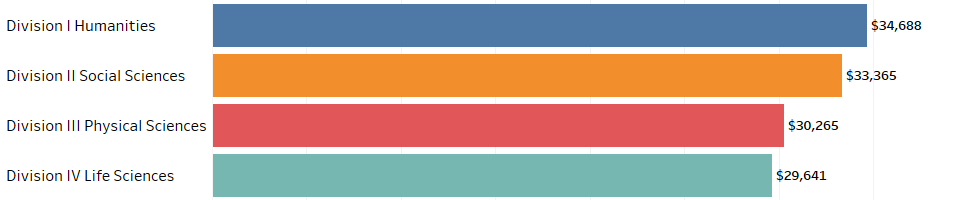

Although base funding is a minimum funding commitment communicated to prospective and current students, many students exceed this level of funding on an annual basis due to income earned through research or teaching assistantships, fellowships, internal and external awards, and other activities. Figure 2 provides an example of annual net income earned by PhD students (year 1-4) in 2020-2021, which is equal to their total university earnings less their tuition fees. When comparing average income rates in Figure 1 and Figure 2, students earned approximately $6,500-$15,000 more from University sources than the amount specified for their base funding commitment.

Figure 2: Average Actual Net Income – PhD students (Year 1-4) in 2020-202124

For some individual students, actual net income can be significantly higher than the funding earned by peers in their program. For example, U of T data shows that a very limited number of PhD students have attained a maximum net income above $125,000. However, it is important to note that these substantial income amounts are not representative of the earnings of the majority of graduate students at the University. Specifically, across all four SGS Divisions, PhD students (Years 1-4) in the 10th percentile have a net income of $18,052-$21,691, while PhD students in the 50th percentile have a net income of $26,489-$33,287, and those in the 90th percentile have a net income of $42,859-$51,546.

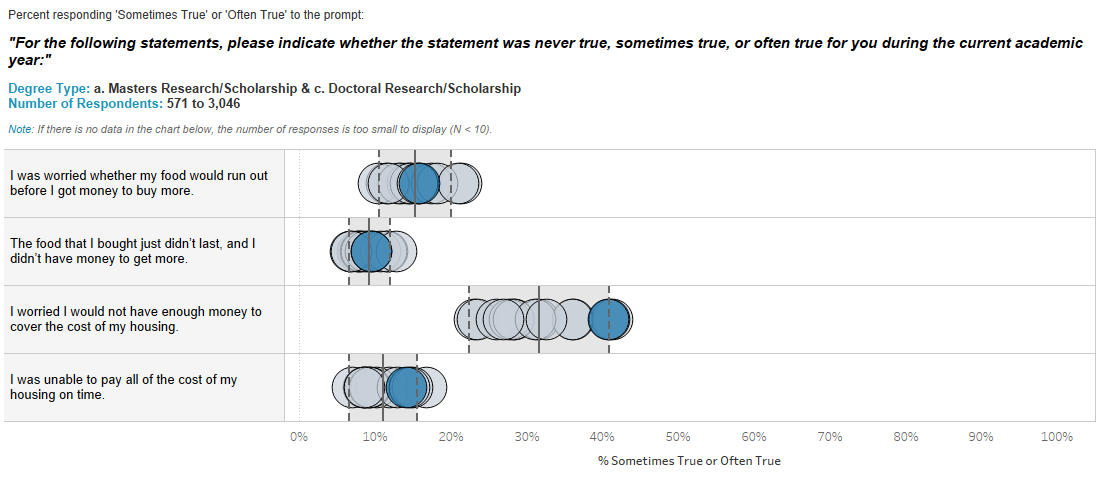

As a result of these funding levels, most graduate students report struggling to cover basic expenses (e.g., housing, groceries, transportation) with the income from their current funding packages. In fact, in the 2021 gradSERU survey, 43.0% of doctoral students at U of T were concerned they would not have enough funds to cover the cost of housing and 16.1% were concerned that their food might run out before they received funds to purchase more groceries. When accounting for year of study, these percentages remained similar for PhD students within and beyond the funded cohort years (i.e., those with base funding packages and those without), suggesting the issue relates to both the amount and length of funding packages. Further, the percentage of graduate students with cost-of-living concerns remains very high when including the perspectives of research-stream master’s students, with 40.9% graduate students (i.e., doctoral and research-stream master’s) anxious about housing costs and 15.9% concerned about food insecurity. When comparing these data points against peer institutions in the gradSERU consortium, U of T graduate students were on par with peers regarding concerns about food insecurity, but stood out with respect to worries about housing expenses (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Research-Stream Graduate Students’ Food & Housing Security Financial Concerns

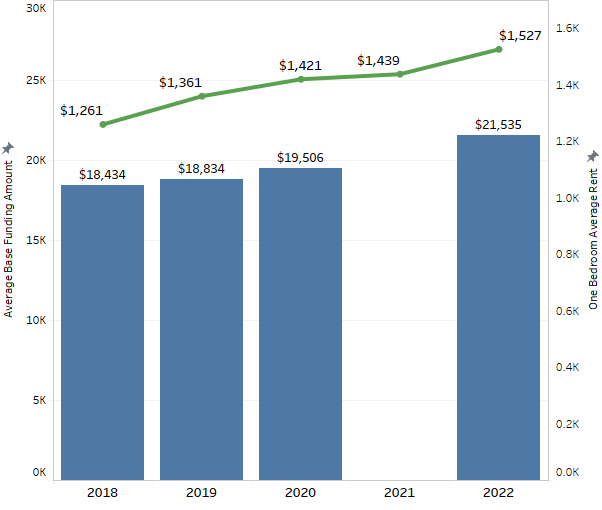

In an effort to address student needs, graduate units have increased graduate funding packages in recent years, though it is evident these efforts have not always kept pace with rising costs. Figure 4 illustrates the increases in average PhD funding against the rising consumer price index and average monthly cost to rent a one-bedroom apartment in Toronto. As evidenced in Figure 4, the average monthly cost of a one-bedroom apartment in Toronto in 2022 was approximately $1,527 ($18,324 annually). When comparing the cost of housing against the average annual base funding amount in 2022, students were left with only $3,200 to cover remaining expenses.

In response to the discrepancies between funding levels and costs of living, many students seek supplementary employment to bolster their income. For example, though full-time students are expected to engage in their studies on a full-time basis and make timely progress toward program milestones, a recent survey of graduate students in Canada suggests 55.6% of respondents have employment outside of their studies, with 36.3% of those students working between 5-20 hours per week.25 Anecdotal evidence from graduate chairs and faculty suggests the need to secure additional employment outside of one’s studies is amplified for students beyond the funded cohort years (i.e., years 5+).

Taking on additional employment outside of graduate studies can be a significant obstacle to students’ academic progress, yet many students feel they must do so to supplement their funding package and support their financial well-being. While the monitoring of students’ hours of employment outside of the University should not be within the University’s purview, the University should endeavour to establish structures and practices to ensure graduate students are able to make full-time, satisfactory progress towards the completion of their graduate degrees, and consequently, improve time-to-completion rates.26

In sum, as the impacts of inflation continue to be felt, equitable access to affordable, high-quality graduate education will remain a significant concern, both for current and prospective graduate students, and for all academic leaders involved in funding-related decisions.

Figure 4: Average U of T PhD Funding vs. Average Monthly Rent for One-Bedroom Apartment and 2018-2022 Ontario Consumer Price Index27

The Funding Package: Eligible Sources of Funds

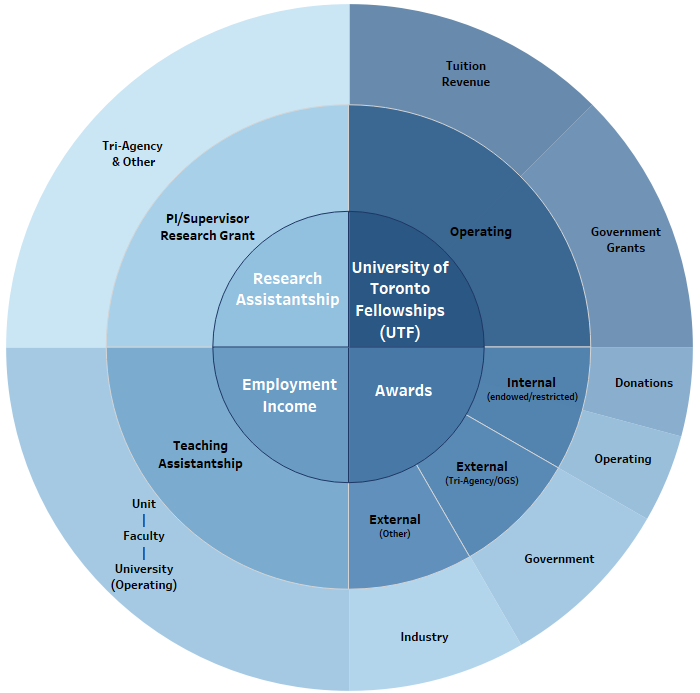

The standard graduate funding package typically comprises one or more of the four components detailed in Figure 5:

- University of Toronto Fellowships (UTF), which are derived from the operating budget of the University, primarily composed of tuition revenues and government operating grants;

- graduate awards, which are comprised of internal awards (e.g., funded from operating and restricted funds from donations) and external awards (e.g., scholarships or research awards funded by the Federal or Provincial governments, primary investigator/supervisor grants, or awards funded by industry);

- employment income (e.g., teaching assistantships, graduate assistantships, and course instructorships allocated from operating budgets); 29 and,

- research assistantships and research fellowships available through primary investigator/supervisor research grants.

Figure 5: Sources of Funding Packages – Conceptual Model

As U of T is a publicly funded institution, the largest components of graduate student funding levels are external to the University (i.e., government scholarships, government research grants to faculty, and tri-agency awards), which presents significant challenges as graduate units aim to increase graduate student funding levels. Without meaningful increases to the value and number of governmental scholarships and research grants over the past twenty years, the University has had to compensate for the gaps in funding with operating resources (see Figure 6). For instance, in 2021-2022, the University provided $365.4 million in financial support to graduate students, including $138 million in fellowships and awards, $83 million in teaching assistantships, $31 million in research stipends from operating budgets, $73 million in external research stipends, and $40 million in external awards.30 Figure 6b displays the same chart using inflation-adjusted dollars, which demonstrates that while average base funding amounts have slightly increased over time, government-funded scholarships have decreased. For the government-funded scholarships available, research suggests that international students and students from equity-deserving groups face additional barriers in attaining external awards to supplement graduate unit funding packages, including eligibility requirements, evaluation criteria, and a lack of representation among those who obtain federal awards.31

In addition to these challenges, some academic divisions and graduate units must also operate under budgetary constraints, which further limits increases to funding packages.

Figure 6: Average U of T PhD Funding Package vs. Government-funded Scholarships

Figure 6b: Average U of T PhD Funding Package vs. Government-funded Scholarships in Inflation-Adjusted Dollars

In some cases, students in the funded cohort will have secured significant fellowships or scholarships from external agencies recognized by the University, such as federal or provincial awards, that may be considered eligible to offset or replace the University’s guaranteed funding commitment.33 Outside of University-recognized awards, graduate units are responsible for determining which additional sources of external funding can or cannot be included in their funding packages based on three pieces of central guidance: Governing Council policy, an SGS Decanal Memo issued in 2017,34 and the SGS Admissions Manual. Under this guidance, graduate units and students are not permitted to waive the University’s funding commitment, which restricts students from opting to self-fund and graduate units from including funds from a third-party agency that has not been approved by SGS or is not recognized by the University. It also indicates that units are permitted to offer prospective students admission on the condition of securing external funding only when there is an approved Memorandum of Understanding in place with the University and the external agency, or when the external agency is approved by SGS. In circumstances where a prospective student has secured funding from an external agency, it is important to reaffirm admissions standards to ensure all students entering the University are appropriately prepared for the rigours and expectations of graduate research and education. In addition, graduate units should have contingency plans in place should the external funds cease to exist or be discontinued at any time during a student’s program.

External awards or financial support from industry groups on an ad-hoc basis can also pose a challenge for graduate units when developing funding packages for their students. Graduate units are restricted from approving industry fully-funding individual students, and instead, are encouraged to consider modernizing the approach to industry funding by developing longer-term partnerships to generate funding opportunities for future students in their programs. As a whole, policies and guidelines related to funding through personal or external sources are in place to ensure fair and equitable access to graduate studies.

In cases where the student is entering the program with an external funding source (e.g., fellowship from an approved agency), the amount of funding must be equal to or greater than the base funding commitment offered by the graduate unit. If the amount is less than the base funding commitment, the graduate unit or primary investigator/supervisor is responsible for providing the remaining funds. Further, if the funding received through an approved or recognized agency ceases prior to the expected funding time frame, the graduate unit or primary investigator/supervisor is responsible for providing the base funding commitment for the remainder of the unit’s typical funding duration (e.g., end of the fourth year of the PhD).

The Funding Package: Offsetting Unit Operating Support and Top-Ups for External Awards

External awards can have a significant influence on the composition of a student’s funding package. When a student receives an external award, it can either augment or replace some or all of the base commitment. For example, when a student secures an internal or external award(s) greater than the base funding commitment, the award value will offset the base funding, usually dollar for dollar. As a result, the students’ funding package often does not change significantly if they earn these awards (i.e., the award is not fully additive to the base funding commitment).

However, some units offer additive funding to students whose external awards might replace a portion of their funding, as a reward to students for their achievement and as an incentive for students to continue applying for external awards. For instance, if a student obtains a $50,000 award in a unit where the base funding commitment is $35,000, the full base funding commitment is not required by the unit, but the unit may still provide an additional $5,000 top-up of funding to the student, who will therefore receive $55,000 of funding for the duration of the award.35

The practice of external funding offsetting the base funding commitment from a graduate unit is not always well received by students, who otherwise may have expected their external award to be fully additive to their base funding package (e.g., $85,000 in the example above). However, the practice is an important tool in ensuring equity and accountability across the institution, as the funding that is replaced by the award in a student’s package can in turn be re-allocated to other students to increase their packages or bring in an additional student. This is one important way to ensure that graduate education is equitable and accessible to a diverse student population, which in turn enhances the graduate student experience for all students. Nevertheless, these practices continue to be a significant source of frustration for students when they feel they are not appropriately recognized for obtaining highly competitive external awards.

Funding by Program Type

While the Governing Council policy clearly articulates that doctoral-stream students must be offered funding, the funding of research-based master’s programs can differ across the University, as it is up to the discretion of the academic divisions or graduate units whether each master’s program constitutes the necessary route to admission for the doctoral program and therefore, should or should not receive partial or full graduate funding. In some instances, graduate units consider their master’s programs to be terminal or quasi-professional and do not provide funding packages to these programs, instead funding their cognate PhD programs for an extra year (e.g., 5 years). In other cases, research-based master’s programs are considered an important step in preparing for the doctoral program and are partially or fully funded. To make this funding determination, it is important for academic divisions and graduate units to clarify the purpose, learning objectives, and outcomes of each master’s program, taking into account the conversion rates from master’s to doctoral-stream.

Some graduate units also offer “flex-time” research-based PhD programs, which allow practicing professionals to earn a PhD on a flexible basis (i.e., full-time in the first four years, part-time thereafter); these programs are also unfunded. Further, a few graduate units have doctoral programs that have some components of research-based doctorates but are considered professional in nature, and as a result fall into the unfunded category, though funding may be made available during the course of the program (i.e., EdD at OISE, DMA in Music, DN in Nursing, and DrPH from Dalla Lana School of Public Health). Given the variety in graduate level education, it is critical for graduate units to assess the aims of their programs and ensure they align with the rationale for providing funding packages.

Levers for Increasing Funding

There are a number of existing levers that may be engaged by the University, academic divisions, graduate units, faculty members, and students to collectively increase the financial support available for graduate research and education, including:

- Increased lobbying of government and external agencies in a strategic and coordinated manner;

- Review and reallocation of University operating funds;

- Review and optimization of resources available in academic division budgets;

- Enhanced contributions from primary investigator/supervisor grants;

- Leveraging of existing industry funding and development of new streams of industry funding;

- Leveraging of restricted funds for internal graduate awards;

- Amplification of fundraising efforts to create or enhance awards, bursaries, or scholarships; and,

- Strengthening incentives for students to seek out and apply for external awards.

Temetry Faculty of Medicine (TFoM) provides an excellent example of an academic division at U of T using the levers available to significantly increase graduate student stipends over a short period of time. As recently as 2019, TFoM offered research-stream graduate students an annual stipend of $28,000.36 Since then, in consultation with graduate students, the faculty created a three-year plan to increase the annual funding available to students in research-stream programs.37 One of the key levers identified by TFoM for increasing funding according to the three-year plan was enhanced contributions from primary investigator/supervisor grants to offset the additional financial support provided to students in research-stream programs.38 By engaging this lever, TFoM was able to increase their annual stipend by over $10,000. In the 2023-2024 academic year, research-stream master’s students will receive an annual stipend of $37,000, while doctoral students will be offered $40,000.39 These graduate student stipends will be the highest in Canada amongst similar degrees and will help TFoM attract top talent and strengthen competition with peer institutions in the United States and abroad.40 In addition to significant increases in graduate stipends, the faculty provides over seventy entrance scholarships and remains committed to discovering additional sources of funding to enhance student financial support.41

Emergence of Decentralized Funding Practices and Associated Challenges

In keeping with its overall budget model, U of T has a decentralized approach to the administration of graduate funding, meaning that graduate funding is managed by leadership in academic divisions and individual graduate units. An approach of this nature has several benefits for a large institution, such as the capacity to leverage discipline-specific knowledge to guide funding-related decisions, the ability to optimize packages according to the available sources of funding in each graduate unit, the opportunity to include funds generated through primary investigator/supervisor grants, and the potential for increased responsiveness to changes in funding levels and practices at peer institutions (which can differ based on academic discipline). Despite these benefits, decentralized practices can also create challenges in funding levels, consistency in application, equity, and communications.

In terms of funding levels, this report illustrates the significant variability across graduate units and SGS Divisions. For example, in 2022-2023, the base funding packages for doctoral-stream programs ranged from $25,554-$33,054 in Division I (Humanities), $25,054-$40,054 in Division II (Social Sciences), $26,054-$40,200 in Division III (Physical Sciences), and $25,304-$35,676 in Division IV (Life Sciences), including the full cost of tuition and living stipends. Based on these ranges, the highest discrepancy between base funding packages is $15,000. Although in dollar terms these base funding packages may be among some of the largest offered in Canada, they are not always competitive in a high-cost market like Toronto where basic living expenses (e.g., housing, hydro, transportation, leisure activities) can exceed $36,000 per year.42 To alleviate students’ financial concerns and enhance competitiveness with other institutions, graduate units and academic divisions must assess current funding practices to identify and optimize the resources and levers available for graduate funding, as well as developing a standard process for review and renewal of graduate funding levels.

The University’s decentralized structure has also produced uneven funding practices across graduate units. A particularly significant example is observed in the integration of major scholarships into funding packages and whether the scholarships are treated as additive or duplicative. Some units offer substantial top-up compensation (e.g., $9,000) above the base funding amount for winning a major award, such as an NSERC or SSHRC (e.g., Canada Graduate Scholarship: Doctoral, Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship), while others offer modest top-ups for the same award ($3,000), or forego top-ups altogether. In another approach, some units prefer not to offer top-ups at all, but instead provide funding support for a year beyond the typical funding duration (e.g., cover the cost of tuition and provide additional $2,000). There are also units where the value of the scholarship only replaces the living stipend portion of the funding package, and the student receives the full scholarship, plus tuition, and a $5,000 top-up.

Variability in top-up practices and replacement funding can lead to confusion, stress, and frustration for students as they attempt to navigate which sources of funding can be additive to the base funding package and ensure they have sufficient and sustainable funding to support their academic pursuits. Inconsistent top-up policies can also disincentivize students and by extension, their supervisors, from seeking external sources of financial support, as the effort required to find opportunities and develop a competitive application can be disproportionate to the reward. In light of these concerns, academic divisions and graduate units must develop a more principled and coordinated approach to top-ups, with stronger incentives for students to seek external awards. It is imperative that students feel adequately rewarded for the successful attainment of external funding.

At times, decentralization can also complicate the disbursement of funds to students because large amounts of it are administered locally by various entities rather than centrally by the University. While some University-wide awards and external sponsorships involve institutional administration, most graduate funding is handled through diverse methods and systems. This leads to challenges such as transparency, payment-deadline adherence, monitoring, reporting, and timely disbursements. For example, some students receive funding packages (including full tuition coverage) over 12 equal monthly installments, which means they may not have sufficient funds to cover their tuition fees by the payment deadline. A lack of streamlined processes for disbursement of funds can contribute to student stress, missed deadlines that result in unnecessary fees, overpayment and subsequent pay-back, and/or late reception of income.

Further, U of T also struggles with a paucity of clear, overarching institutional knowledge related to funding practices and the effects of turnover of academic leadership, something that is common in higher education institutions. Without comprehensive institutional knowledge and subsequent education, it is difficult for academic leaders to fully grasp the landscape of funding in the University, understand possibilities and mechanisms to improve funding, and implement meaningful change in their academic divisions or graduate units within the time constraints of a Decanal or Chair term. In addition, transparent communication regarding graduate funding and financial support is a major challenge across all aspects of decentralized funding practices.

In order to enhance transparency, academic leadership and graduate administrators need to identify and clearly articulate the overarching framework of graduate funding and associated practices within their purview (e.g., top-up practices), be honest with prospective and current students about actual annual income and the time frame of the degree (e.g., normative time to degree), and seek alignment with other units in the University on funding terminology and practices, where possible and feasible.

The U of T is consistently ranked among the top ten public universities worldwide, and has an international reputation for research excellence, innovation, and graduate education. Graduate students are critical to this success. If the University is to maintain and enhance its competitiveness with peer institutions, it must be able to attract and retain the most talented students, and make sure that they feel supported throughout their graduate journeys, as they engage in cutting-edge research and training. We hope that improving financial support will have knock-on benefits, including improved graduate student mental health, productive faculty-student relationships, and the recruitment of an increasingly diverse student population.

Stakeholders across the graduate community recognize that they must take action to address the current flatlining of government funding for graduate research and education and to optimize the available resources to increase support for graduate students. We hope that this report provides a roadmap of graduate funding at U of T and demonstrates a comprehensive overview of possibilities, challenges, and limitations for improving graduate funding. It is incumbent upon all stakeholders, including graduate students, faculty members, administrators, and academic leadership, to acknowledge the scope of their influence in enhancing graduate funding and to make a concerted effort to execute their responsibilities. It is only through this collaborative, University-wide approach, that we can ensure a positive, fulfilling, and supportive graduate community, built upon a mutual commitment to fostering success in graduate research and education.

1 Sourced from 2021 gradSERU survey.

2 2021 gradSERU.

3 2021 gradSERU.

4 Langford, W., & Carstairs, C. (2023). The high cost of inadequate funding for grad students. University Affairs.

5 U15 Submission to the Standing Committee on Finance Pre-Budget Consultation in Advance of the 2023 budget.

6 U15 Canada Statement (March 28, 2023): U15 Canada is deeply concerned about lagging research investments in Canada, sees hope in Bouchard report.

7 Langford et al. (2023).

8 U15 Canada Statement (March 28, 2023).

9 Sourced from the 2023 Report of the Advisory Panel on the Federal Research Support System prepared for the Government of Canada.

10 2023 Report of the Advisory Panel on the Federal Research Support System.

11 Buller, R. (2022). Funding disparities are pushing Canadians to enrol in U.S. doctoral programs. University Affairs.

12 Bresge, A. (2023). U of T scores top marks in QS World University Rankings by Subject. U of T News.

13 Bresge, A. (2023).

14 Including a reliance on publicly available information as well as contextual factors (e.g., costs of living in a specific city, increases or decreases to funding over time, funding structures and administration, and discipline-specific cognates).

15 Laframboise, S.J. et al. (2023). Analysis of financial challenges faced by graduate students in Canada. Biochemistry and Cell Biology, 00, 1-35.

16 2021 gradSERU: 49.5% of students reported being concerned, very concerned, or extremely concerned about being able to pay off loans. For cost of education (i.e., “how concerned are you about paying for your graduate/professional education next year?”), 40.6% said they were concerned, very concerned or extremely concerned. For food and housing security: 15.5% indicated it’s often or always true that they are worried about whether their food would run out before they got money to buy more, while 37.2% indicated it’s often or always true that they worried they wouldn’t have enough money to cover the cost of their housing. 13.9% said it’s often or always true that they are unable to pay all of the cost of their housing on time.

17 Sourced from Temerty Faculty of Medicine Graduate Representation Committee 2022-2023 Finance & Living Expense Report.

18 Langford et al. (2023).

19 GRC 2022-2023 Finance & Living Expense Report.

20 2021 gradSERU.

21 https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/policies/student-financial-support-policy-april-30-1998

22 https://planningandbudget.utoronto.ca/operating-budget/

23 https://sgs.calendar.utoronto.ca/programs-graduate-unit

24 Sourced from Student Accounts – Planning and Budget Office

25 Laframboise, S.J. et al. (2023).

26 https://cou.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/OCGS-Principles-for-Graduate-Study-at-Ontarios-Universities-October-2021.pdf

27 Average monthly cost of one-bedroom apartment in Toronto sourced from: Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

28 In an effort to increase graduate funding transparency, SGS began consistently collecting data and reporting on base funding packages in 2018. SGS has committed to sharing this data on a biennial reporting schedule. Institutional policy requires graduate units to publicly report base funding information on their websites on an annual basis.

29 Personal employment income outside of the examples listed does not count towards the funding package.

30 Sourced from: 2021-2022 Annual Report on Student Financial Support. Please note: the amounts above are listed in aggregate; a more specific breakdown of financial support can be found in the report.

31 Baskaran, S., et al. (2021). Improving the accessibility of Federal Graduate Research Awards in Canada. Journal of Science Policy & Governance, 18(4).

32 In an effort to increase graduate funding transparency, SGS began consistently collecting data and reporting on base funding packages in 2018. SGS has committed to sharing this data on a biennial reporting schedule. Institutional policy requires graduate units to publicly report base funding information on their websites on an annual basis.

33 Examples of such scholarships include University Health Network, Athlete Assistance Program (Sport Canada), and CONACyT (Mexico).

34 SGS Decanal Memo: Guidelines for External Funding (April 2017)

35 Please see an example created by the Faculty of Arts & Science to illustrate the varying composition of funding packages and associated top-up practices. How Graduate Funding Works in A&S: https://www.artsci.utoronto.ca/graduate/graduate-funding/how-graduate-funding-works. Also included in the Appendices.

36 https://temertymedicine.utoronto.ca/news/temerty-medicine-increases-graduate-student-stipends

37 https://thevarsity.ca/2023/01/23/temerty-medicine-increases-graduate-student-stipends-for-2023-24-academic-year/#:~:text=For%20students%20enrolled%20in%20a,will%20be%20%2440%2C000%20per%20year.

38 https://temertymedicine.utoronto.ca/news/temerty-medicine-increases-graduate-student-stipends

39 https://temertymedicine.utoronto.ca/news/temerty-medicine-increases-graduate-student-stipends

40 https://temertymedicine.utoronto.ca/news/temerty-medicine-increases-graduate-student-stipends

41 https://temertymedicine.utoronto.ca/news/temerty-medicine-increases-graduate-student-stipends

42 https://studentlife.utoronto.ca/task/living-costs-in-toronto/

Download a PDF copy of the report

2. A Community-wide Approach: Considerations & Recommendations for Enhancing Graduate Funding Practices

SGS Graduate Funding Working Group

School of Graduate Studies

Fall 2023

Table of Contents

In the Fall of 2022, the School of Graduate Studies (SGS) struck the SGS Graduate Funding Working Group. Chaired by Dr. Joshua Barker, Vice-Provost, Graduate Research and Education and Dean of SGS, the working group was formed to collectively enhance understanding of the graduate funding landscape at the University of Toronto (U of T) and identify a series of funding considerations and strategic recommendations that academic divisions and graduate units could employ to attract and retain talented students and engage in best practices to support students throughout the course of their graduate programs.

The SGS Graduate Funding Working Group membership included senior academic and administrative leadership, University counsel, graduate students, and institutional administrators across the three campuses:

- Joshua Barker (Chair), Dean, School of Graduate Studies, Vice-Provost, Graduate Research and Education

- Dwayne Benjamin, Vice-Provost, Strategic Enrolment Management

- Suzanne Cadarette, Associate Professor, Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy

- Rachael Ferenbok, Associate University Counsel

- Jessica Finlayson, Financial Officer, Graduate Operations, Faculty of Arts & Science

- Dionne Gesink, Associate Dean, Academic Affairs, Dalla Lana School of Public Health

- Antoinette Handley, Vice-Dean, Graduate Education, Faculty of Arts & Science

- Mindy Harris, Director, Academic Programs & Operations, OISE

- Sarfaroz Niyozov, Acting Associate Dean, Programs, OISE

- Normand Labrie, Associate Dean, Programs, OISE

- Rene Harrison, Vice-Dean, Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies, UTSC

- Tina Keshavarzian, Graduate Student, Temerty Faculty of Medicine

- Kelly Lyons, Acting Vice-Dean, Research and Program Innovation

- Jeff Packman, Associate Dean, Graduate Education, Music

- Ajay Rao, Vice-Dean, Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs, UTM

- Mike Snowdon, Manager, Academic Planning & Analysis, Planning and Budget

- Julie Audet, Vice-Dean, Graduate Studies, Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering

- Craig Steeves, Acting Vice-Dean, Graduate Studies, Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering

- Alexie Tcheuyap, Associate Vice-President and Vice-Provost, International Student Experience

- Annabel Thornton, Graduate Student, Economics

- Justin Nodwell, Vice-Dean, Research & Health Science Education, Temerty Faculty of Medicine

The working group met five times over the course of the 2022-2023 academic year and engaged in a variety of measures to strengthen understanding of graduate funding and inform proposed recommendations, including: reviewing current policies and practices in graduate student funding across the institution; exploring student experience data, current issues, and associated implications for all stakeholders; assessing U of T’s funding support in relation to peer institutions in Canada and abroad; and identifying the existing institutional levers for improving graduate student funding levels. Through the review of data, synthesis of institutional knowledge, and subsequent discussions on funding practices, members of the working group were provided with an opportunity to reflect, develop strategies, and share best practices to improve graduate funding at the University. Throughout their discussions, working group members shared their deep concerns on the current state of graduate funding and emphasized the importance of building infrastructure to support coordination among academic divisions and graduate units.

To capture the institutional knowledge of graduate funding at U of T created through the working group and provide a framework to guide funding-related decisions and practices moving forward, the working group developed three key outputs:

- A comprehensive educational report that provides an overview of the current state of graduate funding in Canada, outlines policies and practices within U of T, and identifies the challenges and opportunities for graduate funding in a decentralized context.

- A set of institution-wide funding considerations to facilitate alignment and interdisciplinary collaboration, where possible, and frame future graduate funding decision-making processes.

- A list of recommendations that explore solutions, address ongoing issues related to graduate funding within graduate units and across the University more broadly, and identify the stakeholder responsible for stewarding the recommendations to fruition.

The funding considerations and recommendations developed by the working group are designed with each stakeholder in mind and serve as a coordinated strategic approach to improving the infrastructure of graduate support.

For the purpose of the report, funding considerations, and recommendations documents, the following key terms are defined as follows:

- Academic Divisions: The University’s academic programs are organized into 18 faculties and divisions (i.e., Academic Divisions). Within each Academic Division, there may be departments, colleges, centres, and institutes that provide further support for study and research in focused areas. A list of the 18 faculties and divisions can be found at the following website: Academic Divisions.

- Graduate Units: An administrative entity headed by a graduate chair who has been appointed under the PAAA and housing graduate programs that:

- provides the central structure to house and support graduate programs; and

- includes graduate faculty members, who may be drawn from multiple academic units, as well as graduate students, and administrative staff.

Every graduate unit is assigned a specific budgetary academic unit (“budgetary home”) to act as its administrative and governance home. For a list of programs by graduate unit, visit the following website: Programs by Graduate Unit.

- SGS Divisions: The School of Graduate Studies allocates graduate units into four broad categories: Division 1 – Humanities, Division 2 – Social Sciences, Division 3 – Physical Sciences, and Division 4 – Life Sciences. To determine which programs fall under each category, visit the following website: Programs by SGS Division.

- Base Funding: refers to a graduate unit’s minimum funding commitment to each student per year, including tuition costs and annual living stipend, during the funded portion of the program.

- Funded cohort: refers to a group of students enrolled in a graduate program for whom there is an institutional commitment to provide funding packages throughout the duration of their published program length.

- Top-Ups: When a student receives an award, it can either augment or replace some or all of the base funding commitment from the graduate unit, usually dollar for dollar. To reward students for their achievement, some units offer additive funding – referred to as top-ups – to students whose external awards might replace all or a portion of their funding. The practice of offering top-ups to students who receive awards varies across academic divisions and graduate units.

There are several overarching themes that emerged from the discussions of the Graduate Funding Working Group that may assist in framing the funding considerations and recommendations:

- Graduate funding is an increasingly complex issue that requires urgent attention and a collaborative spirit by all stakeholders across the University to improve funding practices and provide appropriate and sustainable financial support to graduate students. Improvement of graduate funding is imperative to ensuring equity and access to graduate education and attracting the brightest, most talented students worldwide to our graduate programs.

- There are significant constraints to improving graduate funding, but there are also existing institutional levers and resources that can be leveraged to strengthen financial support for graduate students. Academic divisions and graduate units must assess current funding practices to identify and optimize the resources available.

- The determination of funding levels and accountability for meeting funding commitments should remain the responsibility of graduate units and academic divisions, however, it is recommended that steps be taken to increase alignment and coordination on graduate funding practices across the University.

- It is necessary to enhance clarity, transparency, and “truth-in-advertising” about graduate funding through a variety of activities, including the provision of annual SGS-led education related to funding practices for all stakeholders (i.e., students, academic leaders, administrators) and clear, ongoing departmental and divisional communications.

- Academic leadership and institutional administrators must prioritize timely, high-quality academic progress and support lower time-to-completion rates for graduate students to ensure students are funded to the completion of their research-stream graduate degrees.

The following graduate funding considerations are not ranked. Instead, all considerations should be interpreted as equally important, and each consideration will be applied in different magnitudes across the recommendations of the working group.

- Providing support to enter and complete program.

- Enhancing institutional competitiveness.

- Promoting equity, access, and inclusion.

- Recognizing merit.

- Protecting academic freedom and integrity.

- Encouraging academic progress toward degree completion.

- Providing continuity and predictability of funding.

- Considering student needs and personal financial circumstances.

- Increasing transparency in funding practices for students and academic divisions.

- Affirm decentralized approach – framed within an overarching coherent and holistic university-wide funding policy – to setting graduate student funding package levels and graduate unit accountability for meeting its funding commitments.

- Reaffirm the principle that PhD programs need to be funded for the minimum program length.

- Affirm principle of equity of access to funded programs (i.e., no direct or indirect self-funding) and affirm financial need is not a condition of graduate funding.

- Review the Governing Council policy on Student Financial Support to determine if any updates are required.

- SGS should conduct an environmental scan of the funding practices and associated communications of other universities to assess the competitiveness of U of T funding packages compared to peer institutions.

- With guidance from SGS, academic divisions should review all master’s programs and assess the programs’ funding status, taking into account the conversion rate from master’s to PhD.

- Fold regular review of research master’s funding by program type into the UTQAP process and update the list of research-stream programs in the Governing Council financial aid policy document. (The extant list is from 1998.)

- SGS should undertake a review of the flex-time program status: Institute a working group to better understand the nature of the program, its rationale, uptake, and student and program outcomes. Ensure the working group includes people who have had experience with the flex-time PhD model.

- Move away from monitoring graduate student income and toward a focus on academic progress to improve time-to-completion.

- There should be a concerted and continuous effort by all academic divisions and units to ensure that students are making timely academic progress and completing their studies in an appropriate time frame as a means of enhancing funding available in years 1-5.

- Academic divisions should review funding packages annually with consideration of core principles and available resources.

- SGS should provide data and best practices advice to support these reviews and support improved communication about funding packages and top-ups.

- SGS should hold an annual coordinating meeting for graduate/associate deans to report on academic divisional funding levels and top-up practices.

- SGS, in collaboration with the University Registrar’s Office and Planning & Budget, should review Graduate Tuition Fees Assessment Practices and develop recommendations to explore per term billing and to address and clarify minimum degree fees and balance of degree fees issues and practices.

- SGS should reinforce existing best practices and develop a set of guidelines for administrators regarding the disbursement of graduate funding, including the development of internal practices to review students’ funding upon completion to ensure stipend and tuition amounts disbursed are proportional to the period of registration and final tuition invoiced to the student.

- SGS should work with Student Receivables & Accounting Office, Planning & Budget, and other stakeholders to develop a formal tracking mechanism to allow for increased transparency and accurate reporting when students have funding issued by a third-party sponsor (paid to Student Receivables) or by an external funding source (paid direct to student).

- SGS, OVPRI, Government Relations, and Advancement should develop a coordinated approach to increase core components of graduate student funding (scholarships, grants, industry, etc.) and academic divisions and Advancement should determine targeted fundraising strategies to increase support for graduate research and education in their graduate units.

- SGS and Planning & Budget should create an ad-hoc support team to assist academic divisions in optimizing the resources they have available for graduate student funding (e.g., restricted funds, PI contributions). Other offices across the University (e.g., University Registrar’s Office) should be consulted, as needed.

- Academic divisions, in collaboration with SGS, should strengthen incentives for students to seek out award opportunities by developing a more principled approach to top-ups and enhancing education on the professional benefits and pedagogical purposes of external awards. Students should feel they are adequately rewarded for the successful attainment of external funding.

- Academic divisions, in collaboration with graduate units, should examine their restricted funds and utilize available funds (or redeploy existing funds) to expand financial award opportunities for international students.

- Academic divisions, in collaboration with graduate units, should continue to foster the University’s commitment to inclusive excellence and equitable access to graduate education by expanding financial award opportunities for graduate students from underrepresented groups.

- SGS, in collaboration with an expert panel, should examine the SGS Tri-Agency algorithm and associated processes to increase standardization in application procedures, ensure a fair and rigorous assessment of applicants, and enhance competitiveness of U of T graduate students.

- Affirm principles related to industry funding and ensure components of units’ funding packages are connected to students’ training and progress through the program. Contingency plans should be created by graduate units and academic divisions to ensure continuation of funding for individual students with external support, if issues or challenges arise that jeopardize their funding sources.

- SGS should create a set of principle-driven and transparent criteria to assess eligible external funding sources. Criteria should include a review of factors such as the value and duration of support, demonstrated history of student support, potential risk to the institution, alignment with university’s academic mission/freedom, and principles of EDI.

- SGS should review the current admissions policy, with attention to conditional offers based on securing funding from external funding sources.

- SGS should enhance its communications about graduate student funding and provide an annual workshop on graduate funding for decision-makers.

- SGS should collate best practices, develop templates, and offer guidance on funding-related communications to support graduate units. Graduate units should clearly communicate their funding and top-up practices on their websites, in their graduate student handbooks, and through an annual funding letter.

- SGS should play a convening role in creating best practices/guidelines for all graduate funding-related communications, including template communications units can use.

- SGS should create a working group to better understand and communicate the funding opportunities available for students in professional programs, as well as advise on the development of recognition programs and opportunities for students that honour their achievements and help them strengthen their CVs.

Download a PDF copy of the report